Man on a Mission: How Brian Belle-Fortune fought for Jungle / Drum and Bass in the Mass Media

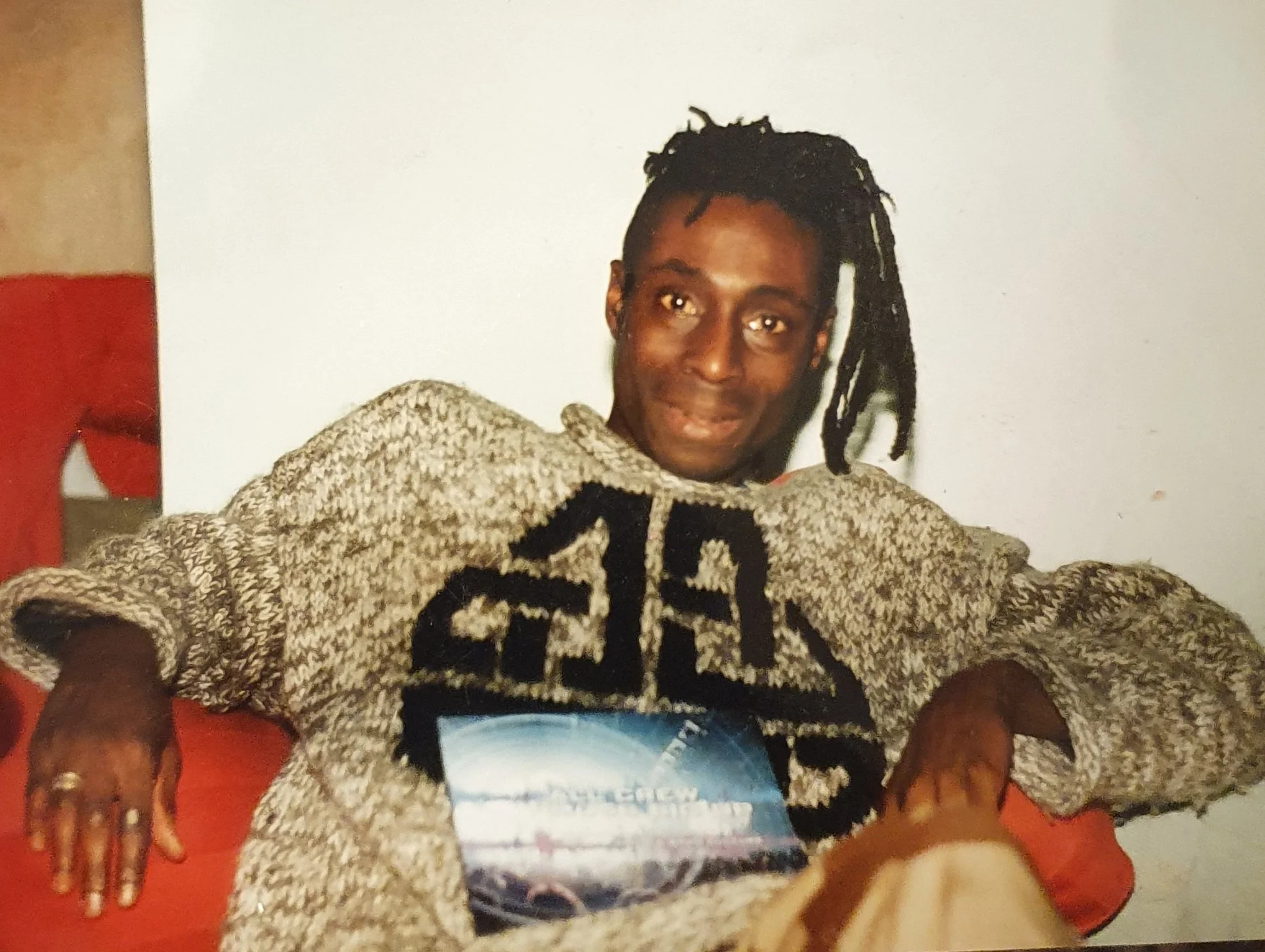

Brian in 2000, with his original copy of All Crews.

Jacob Tucker (Polyphemus) interviews All Crews author Brian Belle-Fortune about how race, class and access shaped his experience working for MTV and the BBC in the 90s, and unpacks the narrative of Jungle / Drum and Bass as ‘Black music’.

For a new generation of Junglists like myself, you can’t help but feel like you missed out on something. The ‘glory days’ of Telepathy and Roast, AWOL and Jungle Fever. It’s easy to get sucked into nostalgia, but few things can take you back in time like Brian Belle-Fortune’s All Crews, a colourful, and all-encompassing snapshot of an entire scene, warts and all.

The book itself has a story much like Jungle / Drum and Bass itself, an against-the-odds effort to survey all the influences and infrastructure that goes into making a real scene, a real culture. In the build-up to the release of a freshly updated version of All Crews, I went to Tottenham to speak to Brian Belle-Fortune about his own journey through the world of Jungle / Drum and Bass.:

Jacob: How did you go about writing All Crews?

Brian: Well, it was my first book. Before that, I had done One in the Jungle, I worked for MTV, and in my personal life, I trained as an intensive care nurse. I was at St Bartholomew’s, and I was having a crisis of thought: I loved my job, but for it to be really busy then people have got to be, you know, dead and dying. I kind of thought, hang on, that’s a bit of a sick way to think, and I left nursing for a while. I went to work in the media because I thought that might be lovely and glam, but then, there was a moment where I really thought ‘what the fuck am I doing here? Listen you lot, I'm going. I've got patients to look after.’

I left the media job at MTV but had a meeting with the BBC producer of Modern Times and wanted to get a documentary made about Jungle / Drum and Bass. So, I had a conversation with him and realised I had all of this information in my head, and I needed to sit down and start writing.

Jacob: In All Crews, you really get a sense of the whole ecosystem of Jungle, and I think that's something that we're almost missing today with a very DJ-centric approach to it. I think maybe in part because it's not in the industry’s favour to make themselves visible but it's really amazing the sense for the whole infrastructure that you get from All Crews.

Brian: You know, I occasionally read reviews. One of them said something about ‘Brian Belle-Fortune’s somewhat chaotic book.’ So I thought ‘Right okay then, you see chaos, I see order’. Speaking to some of the artists as well, GQ would say ‘man, you’ve just gone through everything clinically, just dissected the whole thing.’

Jacob: I know in All Crews you talk about driving around the M25 and being part of all that. I notice that later on you get a bit of a conflict between the people who had been raving in ’88 and ‘89 and the people who came into Jungle later, in maybe 92’ or 93’?

Brian: They were completely different generations, even in that very short space of time. People were very much in their clubbing silos, so the soul and rare groove lot did not like the new ravers. I do remember one time where I had gone to a rave but was going to a soul / rare groove club. I had this T-shirt which was obviously like a rave T-shirt and this guy, who was handing out flyers, was very reluctant to hand me a flyer, a Black guy like myself. He missed me out and I reached to get the flyer and he goes ‘well it's nothing like that sort of thing you know,’ referring to my t-shirt.

There’s a great bit in the update to All Crews, from an interview with Fabio, where he remembers that him and Grooverider were in their usual record shop in Brixton and Grooverider said, ‘so anyway, Soul’s dead man.’ Fabio said that they had to practically run out of the shop, or else they would have got hit by somebody!

Jacob: When when was that?

Brian: That would have been the very late eighties, and some black people did not like the rave scene at all. But then again, how many people had actually been out and experienced it? The newspapers were full of sensationalist stuff.

Jacob: Where did the reggae and dancehall people sit in that?

Brian: I think it took a newer generation of Black kids who were born here, as opposed to the Black kids who came over here from the Caribbean or back in the 60s. I understand this now in retrospect but not at that time. There was a real thing of: you were born here, your parents weren't born here, but your parents are struggling to understand what their kids’ lives should be. It should be exactly similar to their own lives but then they find that if you’re born here and you go through the school system here, there’s all these horrible barriers and you have to learn to live and negotiate life in a different way, which to me meant understanding or being part of the music, just being English.

I just smiled then ‘cos I was thinking about Lenny Henry and Lenny Henry’s mum saying: ‘it’s ‘bout integration.’ You have to integrate, and so as kids, we did. Otherwise, you just wouldn’t get on at school.

Jacob: That leads to another question I wanted to ask you. Is there anything that, through writing All Crews, you changed your mind about?

Brian: I think the ideas had been forming for decades, so when I sat down to write that's what came out. I didn’t go and consult any books or ethnography. I just figured it out for myself, and then you realise later when speaking to Black people that we all had to figure out the same journey.

I don’t think I’ve changed my mind hugely; it's more or less confirmed the natural feeling that I had that when they talk now about this diversity of colour and sexuality, it's also diversity of opinion and being able to make a different decision than my parents would have done, or that I would have to trot out a line that would have been expected of me.

Jacob: how do you feel about the recent movement to reclaim Jungle as black music?

Brian: I know what you’re talking about, because we had all that Ragga Jungle, or what became known as Jungle, sort of like 92’ to 95’, 96’ and then there was a backlash against that. A backlash against that reggae kind of ethos, and then we started to get more Drum and Bass, and less Jungle, so I think that a lot of the conflict is about a clash of cultures. But also, people kind of get bored of a sound.

I think we really have to understand that from the beginning this is Black music. I'm just concerned about the ‘reclaiming’. Jungle / Drum and Bass, as a music form, goes through different life cycles. It obviously went very kind of Drum and Bass-y and lost a lot of the soul and funk of the music but then it changed into different forms. I think people can claim it as their own. They can't claim that they invented it, but they can identify with it and say this is what the music says to me.

Things get complicated when people start to categorise and put things in boxes, because then you're in the box over there and you can't really do that or you’re not supposed to like that, and I think the whole point of the music is to accept different kinds of influences. I don't know what that person over there is going to contribute. I don't know how they’ve grown up musically. I'm very interested to see what they make of this music genre.

Jacob: I know that for a lot of Black Jungle / Drum and Bass artists, DJs, and producers, often that label, especially in the 90s, felt like a sort of boxing in. What groups like the Black Junglist Alliance are trying to do is to show that Black doesn't just mean Ragga and Reggae, it can be a whole host of things.

With Jungle / Drum and Bass you are always going to say, ‘you shouldn’t do that’ or ‘that shouldn’t be in that direction’, but it’s about freedom. I was quoting Jazzie B only yesterday and his lyrics: ‘fair play but it's all about expression.’ It’s a free space and everybody’s allowed to contribute. I don’t know if it's really valid for anyone to come along and say, ‘that's when it stopped being Jungle / Drum and Bass.’

Jacob: You make a very conscious effort to call it Jungle Drum and Bass. I can't say it's been the most successful project, although I admire your dedication! Do you feel that people are understanding your choice more or do you feel like there's now even more of a division between Jungle and Drum and Bass as two different things?

Brian: Ooh, that’s a messy one. The use of the word, or the explanation varies depending on who you’re speaking to. In this context, I will use Jungle and Drum and Bass interchangeably but then if I want to talk about history and what was going on sort of mid- to late-nineties, I have to say ‘that was a bit more Jungle’ because it was the epitome of what came to be known as Jungle. Because there was this explosion in ’94, ‘95 and the media got a hold of it, terms got banded around and what was Jungle was supposed to have died in ’96 and ’97. Then, the music had become much more Drum and Bass, removing the Ragga and Reggae samples.

Jacob: how much of an impact do you think the media discussions had on the scene or did you think they were sort of a reflection of splits that were already occurring?

Brian: It got complicated because where there was Jungle being played and you had a certain kind of person going, they may have been responsible for the violence. A lot of the violence that took place, though, was the sort of violence that would have occurred with any new music genre. I just remember the phrase ‘devil music’, and that’s why the bloke didn’t want to give me a flyer, I was wearing the wrong kind of T-shirt!

Jacob: satanic!

Brian: And it really was this kind of ‘devil music’. I think a lot of these terms were kind of slippery. In a way you’re talking about something that’s coming not from academia, it’s coming from the street and street terminology is very pliable; it depends on who you’re speaking to. It’s come from Black music, it definitely has, but what you then do with it, when you're making it, it’s up to you.

Jacob: I see an interesting shift. In the 90s it seems like you wrote All Crews because you were frustrated with a prescriptive idea of what Jungle was from institutions like the BBC. Now, 30 years later, we're having to shout about the history again, because that has been lost.

Brian: I think I was passionate about music, I had gone out and done the raves, the M25, but once you get into these organisations like the BBC, like MTV, I saw they had their own idea of what Jungle / Drum and Bass is. I went into TV to get the proper story across, and I found it really quite difficult to do that once I was in those organisations.

Jacob: How did you navigate those sorts of challenges? Inevitably you can't win every battle.

Brian: It was a fucking nightmare. In a way, if you break this down, thinking about my involvement with Jungle and the BBC, and thinking of the name even, ‘One in the Jungle,’ it was very much a mission: we’ve got to get this music on to Radio One. I didn't necessarily expect the outcome but when it did happen it was a dream come true, it really was.

I would be between the Junglists and the media, and if you didn't do things in the right way you weren't going to get access. The Junglists would say, ‘we’ll do the interview but how much are you gonna pay us?’ and we said, ‘well, it doesn't really work like that.’ They replied: ‘Oh yes it does, look at the BBC, they've got loads of money.’ I was dealing with people who didn't necessarily understand the way that programmes get made and get funded. That you have to have ideas and committee meetings before we actually get a budget. When MTV and Radio One wanted to cover the music, they wanted it done as cheaply as possible and so it was very frustrating for me.

The BBC wanted things, and I was thinking ‘okay, if you want this from me, if you want this level of access, you're going to have to pay me for six months so I can sit around and just become a member of the group, because the things you are asking for you do not really get, you will not really get.’

Jacob: So, what sort of things would that be?

Brian: Dodgy things. Sometimes they were trying to find a way to ask me about the criminal side, there was that assumption. There was an assumption, for instance, that maybe a lot of Black people were the same.

I just remember one particular thing: General Levy’s Incredible. There was one woman in an office somewhere, I can’t remember exactly what the scenario was, but she was a lot of fun, and she was trying to understand the words of Incredible. She said, ‘yeah I’ve got this, I’ve got this but what does that mean?’ I'm like looking at her like, ‘listen to my accent, I don't really do patois’.

I think the production team also wanted a certain level of access. They were asking me things and I was like, ‘look guys, I don't hang out with the mandem! I'm sorry, you know, I'm a middle-class, Black guy that went to boarding school.’

It’s quite funny actually. When we made the film Radio Renegades with Brockie and Det, with Kool FM basically, there was the BBC car, with the reporter and the cameraman, and there's this other car with Brockie, Det, good music, and a load of herb, and I can tell you which car I was staying in! And it really did feel like ‘wow, I’m in the middle here.’

Jacob: In your interview with Julia Toppin on Conscious Lyrics, you said people really did want to tell their stories and that you managed to speak to a whole load of people. I remember you also said that after doing One in the Jungle, you gained a lot of credibility, so did you feel like your access changed?

Brian: To a point. After leaving MTV and wondering what I was going to do with my time, DJ Ron offered me a job. He offered me to be the Label Manager of London Some’ting records, who were then based not too far from OId Street, Goswell Road, and I was seen as somebody who was organised, and who could organise somebody’s life. Unfortunately, it didn't work out that way and it ended up in court because he didn’t pay me. But what I did get, and it was worth far more to me and changed the book completely, is the fact that suddenly I was in an environment where people from the Jungle scene were coming to hang out. You’d hear all their conversations, all their adventures, and attitudes to life. I got in touch with Jumpin’ Jack Frost, Kool FM, GQ, and Navigator, and it was the time spent there that basically changed the book and made it what it was.

One of the things that helped me do my interviews was being a nurse. People will tell nurses everything. You’re trained to ask questions, and to let people talk, to let them reveal their own truths or narratives. There was one occasion with DJ Ron, where we were talking for ages and he goes, ‘how'd youhow’d do you do that Belle-Fortune? You do it every time. I just end up telling you things that I’m not supposed to be telling you!’ And I said, ‘well, it was nursing, I learnt it when I was nursing.’ You really learn to speak to whole range of people, so thank you nursing!

Jacob: I remember one snippet where you're in the car I think with Randall and he's playing a bunch of different places on one night, and you try to ask him about the fees, and he says something along the lines of ‘no chance.’

Brian: It’s funny because the producer asked me to ask him and I was kind of like, ‘forget it mate, you ask him he’s not going to talk to about it, and he didn’t.’

Jacob: did you manage to get that sort of information from anyone?

Brian: Yeah, I think what I was trying to do was to get him to say it himself and he wasn’t going to.

Jacob: Too smart for that.

Brian: Jungle / Drum and Bass was very much an informal scene, but you have to actually do business which means formalising some things. If you speak to some of the managers and the booking agents they had to, as far as declaring tax and VAT, find a way of living and earning without giving away too many secrets. ‘Tis often said that Drum and Bass has remained partly underground. It’s a funny scene in that it is overground fully, but it kind of has this kernel of underground energy.

Jacob: You do sort of have the tension between, well, the anarchy of it all, because you have that freedom but that also comes with you know M-Beat not being paid for Incredible or A Guy Called Gerald [not being paid for Voodoo Ray], people running away with money and people not being paid…

Brian: yeah, you had that a lot…

Jacob: …or you!

Brian: Or me! Yeah, you’re dealing with people who are on the edge of things, but I can tell you one thing. I might not have been paid but the DJ's waiting for the cash in brown envelopes after they played their sets, there was a lot of… well I don’t know how much I can give away. It’s like any business, you know, ‘have you got any cash darling?’

We were quite young and energetic when the scene first started, all piling into a car, and going off here, there and everywhere. When you start dealing with managers, and contracts and expectations in broadcasting, you can be a very young novel scene at the beginning, but then you have to do the business to make sure the whole thing doesn’t collapse.

Jacob: and on that more sober note, I would like to thank you very much for speaking to me today.

Brian: It’s a pleasure.

The newest version of All Crews will be published in 2023 by Velocity Press in both print and as an audiobook, so keep your eyes peeled!

Jacob and Brian